Reporting Programs and Requirements

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP) is a federal emissions reporting program which requires high-emitting companies to account for and report emissions at the facility level. Under the GHGRP, facilities emitting over 25,000 MT CO2e per year are required to report their emissions. Approximately 8,000 U.S. facilities are currently required to report direct emissions under the GHGRP requirements. The program asks companies to categorize emissions by process, including stationary combustion and electricity generation. The GHGs regulated under the GHGRP umbrella include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N20), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), and other fluorinated gases. Other companies may opt to use the EPA Simplified GHG Emissions Calculator for voluntary reporting purposes.

Beyond the EPA greenhouse gas reporting requirements, multiple states have launched their own mandatory requirements for carbon accounting, measurement, and disclosure, including California, Oregon, and Washington. Companies based in California and Washington are required to report if they emit more than 10,000 metric tons per year. Oregon has an even lower threshold of 2,500 metric tons, but only certain sectors are required to report. Currently, there are no city-specific GHG reporting requirements, although many municipalities have other forms of emissions reduction targets relevant to specific sectors (such as Local Law 97 in New York City).

Introduction to the Calculator

The EPA GHG Emissions Calculator is a tool that helps organizations estimate their yearly greenhouse gas emissions in the US. It uses the latest guidelines and data from the EPA to calculate emissions. By inputting their activity data, organizations can determine both their direct and indirect emissions for the year. The Calculator allows the user to estimate GHG emissions from scope 1 (direct), scope 2 (indirect), and some scope 3 (other indirect) sources.

There are three primary steps in completing a GHG inventory:

- DEFINE: Start by deciding which parts of your organization and which sources of emissions you want to include in your greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory. Use the “Boundary Questions” worksheet to help identify the relevant sources for your business.

- COLLECT: Gather the necessary data for the defined period, which can be time-consuming and challenging. The Calculator provides help sheets with tips and guidance for collecting data from each emissions source and for managing data in general.

- QUANTIFY: Enter the collected data into the Calculator, which is an MS Excel spreadsheet. The Calculator will automatically calculate and total your emissions, which you can see on the “Summary” sheet.

Operational Boundaries

With regards to emission sources, a typical office-based organization will likely have the following (Scope 1 and 2) emissions sources: stationary combustion, refrigeration and air conditioning, and electricity. For those in the industrial sector, such as pulp and paper, cement, chemicals, and iron and steel, you may have sector- specific emission sources that are not covered by the Calculator. Look instead to the GHGRP, which provides guidance and tools that can aid in the calculation and reporting of these emissions.

If you answer “yes” to any of the following questions regarding Scope 1, that emission source should be included in your Scope 1 inventory.

Scope 1:

- Stationary Combustion: Do you have facilities that burn fuels on-site (e.g., natural gas, propane, coal, fuel oil for heating, diesel fuel for backup generators, biomass fuels)?

- Mobile Sources: Do any vehicles fall within your organizational boundary (e.g. cars, trucks, propane forklifts, aircraft, boats). Only vehicles owned or leased by your organization should be included here.

- Refrigeration and Air Conditioning: Do your facilities use refrigeration or air conditioning equipment?

- Fire Suppression: Do your facilities use chemical fire suppressants?

- Purchased Gases: Do you purchase any industrial gases for use in your business? These gases may be purchased for use in manufacturing, testing, or laboratories.

Direct and Fugitive Emissions from Purchased Gases

The difference between direct emissions from purchased gases and fugitive emissions from purchased gases lies in the way these emissions are released into the atmosphere. Imagine you’ve purchased an industrial gas to use in a fire extinguisher. The primary function of this gas is clear: it’s there to be deployed in case of a fire, releasing a powerful burst to extinguish flames. However, what many might overlook is that even while the fire extinguisher sits idle, it can slowly leak small amounts of this gas over time. These leaks, though seemingly insignificant, contribute to what are known as fugitive emissions. When considering the environmental impact, a company must account for both the emissions that occur when the fire extinguisher is actively used and those fugitive emissions that happen quietly in the background. Together, these aspects provide a complete picture of the greenhouse gases released, helping the company better manage its overall carbon footprint.

Direct Emissions from Purchased Gases

These are emissions that result from the intentional use or combustion of purchased gases. For example, if a company buys natural gas for heating or industrial processes, the emissions produced during the combustion of this gas are considered direct emissions. These emissions are directly tied to the company’s energy consumption and are a significant part of its overall carbon footprint, making them crucial for tracking and reduction efforts. Direct emissions from purchased gases are typically measured and accounted for as part of the company’s Scope 1 emissions under the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP).

Fugitive Emissions from Purchased Gases

Fugitive emissions occur when gases escape unintentionally during various processes, such as during the transportation, storage, or use of the gases, without being combusted. These leaks might happen in pipelines, valves, or equipment where the gases are handled. Common examples include methane leaks from natural gas pipelines or refrigerant leaks from HVAC systems. Fugitive emissions are also considered Scope 1 emissions, but they are often more challenging to measure accurately because they can be difficult to detect and quantify.

In summary:

- Direct Emissions are the result of the intentional combustion or use of purchased gases.

- Fugitive Emissions are unintentional leaks or releases of purchased gases during handling and storage.

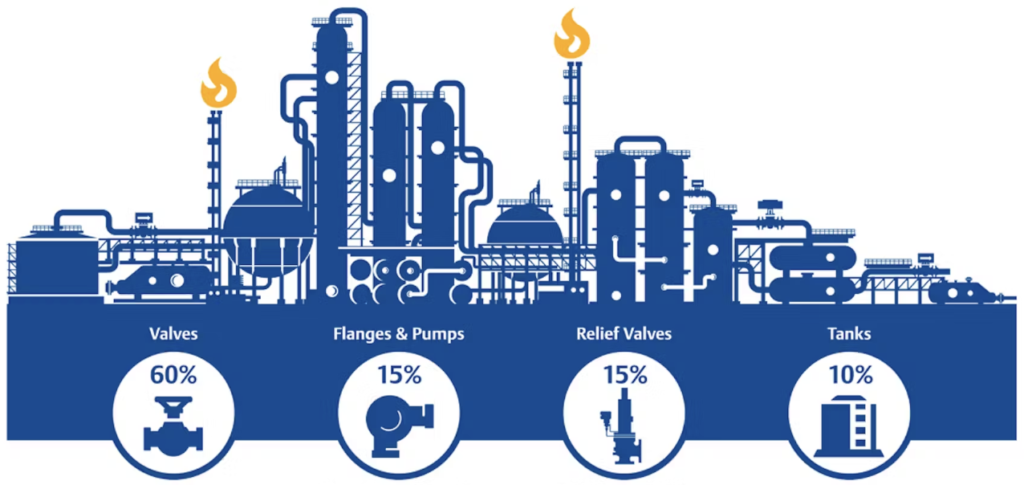

Figure 1 common sources of fugitive emissions

Considerations for Calculating Direct Emissions from Purchased Gases

Industrial (purchased) gases are sometimes used in processes such as manufacturing, testing, or laboratory uses. For example, CO2 gas is often used in welding operations. Since these gases are typically released to the atmosphere after use (i.e. on-site), they are included within the Scope 1 inventory. Any releases of the seven major greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4, N2O, PFCs, HFCs, SF6, and NF3) must be included in the GHG inventory. Ozone-depleting substances, such as CFCs and HCFCs, are regulated internationally and are typically excluded from a GHG inventory or reported as a memo item.

It is assumed that all gas purchased within the reporting period is used and released within that same period. If your business buys gas in bulk for use over several years, you should divide the total amount by the number of years of usage and report that portion annually. Remember to report bulk gas purchases in future years as well. Note that Scope 1 GHG emissions are only those resulting from operations at the reporting organization’s facilities. Emissions that occur during the manufacturing or disposal of equipment or purchased gases are Scope 3 indirect emissions and are not included in an organization’s Scope 1 emissions.

Considerations for Scope 1 and 2 Boundary Definition of Purchased Gases

You may be wondering why the EPA calculator places purchased gases within Scope 1 rather than within the Scope 2 boundary, since purchased electricity and purchased steam both fall under Scope 2. Remember, Scope 1 includes only those emissions resulting from operations at the reporting organization’s facilities (i.e. when the gases are directly emitted from sources that the organization owns or controls). This typically occurs when the organization uses the gases in its operations, and the gases are released into the atmosphere as a result of activities such as industrial processes, refrigeration and air conditioning equipment, and fuel combustion:

- Industrial Processes: If an organization uses purchased gases in manufacturing or other industrial processes, and those gases are released during the process, the resulting emissions are classified as Scope 1. For example, if a company uses a purchased gas like CO₂ in a production process and the gas is emitted during that process, these emissions would be Scope 1.

- Simplified example: use of gases in manufacturing processes where they are released directly.

- Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Equipment: If an organization purchases refrigerants (like HFCs or SF6) for use in their refrigeration or air conditioning equipment, and these gases leak or are released during maintenance, operation, or disposal of the equipment, the emissions are considered Scope 1.

- Simplified example: leakage of refrigerants from air conditioning or refrigeration units.

- Fuel Combustion: If the organization purchases gases like natural gas, propane, or butane and uses them as fuel in equipment like boilers, furnaces, or vehicles, the emissions from burning these fuels are classified as Scope 1.

- Simplified example: emissions from burning natural gas in a company’s boiler.

Generally speaking, to determine whether emissions from purchased gases are considered Scope 1 or Scope 2, you’ll need to evaluate how the gases are used and where the emissions occur within the organization’s operations. If the organization uses the purchased gases in a way that leads to their direct release into the atmosphere (e.g., during industrial processes, as a refrigerant, or in fuel combustion), these emissions are classified as Scope 1.

Scope 1 emissions are only those resulting from operations at the reporting organization’s facilities. For refrigeration, air conditioning, and fire suppression equipment, these emissions may take place during installation, use, or disposal. Refrigerants and fire suppressants may be released from equipment leaks during normal operation or from catastrophic leaks. Also, when equipment is installed, repaired, or removed, refrigerants and fire suppressants may be released if proper recovery processes are not used. Fire suppressants are also emitted to extinguish fires.

Note: Emissions that occur during the manufacturing or disposal of equipment or purchased gases are Scope 3 indirect emissions and are not included in an organization’s Scope 1 emissions.

Scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heating, or cooling. They are a result of the organization’s consumption of energy, but the actual emissions occur at the facility where the energy is generated, not at the organization’s site. If the purchased gases are used by a third party (like an electric utility) to generate electricity, steam, heating, or cooling that the organization then purchases and uses, the emissions from those gases are classified as Scope 2. For example, if a power plant burns natural gas to generate electricity, and your organization buys that electricity, the emissions from the gas are considered Scope 2 for your organization, because the emissions occur at the power plant, not at your facility.

Scope Evaluation Summary for Purchased Gases:

- Evaluate Control and Ownership:

- If the organization owns or directly controls the equipment or process that emits the gases, and the gases are emitted on-site, the emissions are Scope 1.

- If the organization purchases energy (electricity, steam, heat, or cooling) that is generated off-site, and the emissions occur at the energy generation facility, the emissions are Scope 2.

- Consider the Use of the Gases:

- Gases that are combusted, leaked, or released as part of on-site operations are generally Scope 1.

- Gases used by an external energy provider to generate the electricity or heat that the organization consumes are related to Scope 2.

Data Collection Checklist (for all applicable facilities):

- Type of gas purchased

- Amount of gas purchased

- Purpose for the gas

Understanding the ownership and control of the emission source, as well as the type of energy being consumed, will help in accurately classifying emissions as either Scope 1 or Scope 2.

Calculation Methodologies for Direct Fugitive Emissions from Refrigeration, Air Conditioning, and Fire Suppression

Gases coming out of refrigerators, air conditioning units, and fire suppression equipment all fall under the category of fugitive emissions. Fugitive emissions refer to the unintentional release of gases into the atmosphere. The term “fugitive” is used because these emissions “escape” from their intended containment. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) focuses on several fugitive emissions sources that are common for organizations in many sectors: refrigeration and air conditioning systems, fire suppression systems, and the purchase and release of industrial gases – each with their own tab within the EPA calculator. Refrigerants are special substances used in cooling systems like refrigerators, air conditioners, and heat pumps. Their primary job is to absorb heat from one area and release it in another, helping to create a cooling effect. Fugitive emissions from refrigeration can also occur within the supply chain (e.g., refrigerated shipping vessels), or emissions from aerosols, solvent cleaning, foam blowing, or other applications. Refrigeration and air conditioning equipment emissions are consolidated into the same tab within the calculator, since they use the same types of gases. Calculating these emissions follow similar methodologies as for fire suppression, so we’ll review these methodologies together. We’ll review purchased gases in a separate section.

To estimate emissions from (A) Refrigeration and Air Conditioning and (B) Fire Suppression, organizations are provided with three methods, each varying in complexity and data requirements. Listed from most (1) to least (3) preferred, these are:

- Material Balance Method

- Simplified Material Balance Method

- Screening Method

Material Balance Method

The Material Balance Method is the most detailed and preferred approach for estimating emissions by tracking total gases stored and transferred within the organization. This method is recommended for organizations that maintain their own equipment and requires available data on the total inventory of sources (refrigerants, fire suppression gases, etc.), at the beginning and end of the reporting period, purchases during the reporting period, and changes in total equipment capacity.

Imagine you’re baking a cake. You start with a certain amount of flour, sugar, eggs, etc. If you know exactly how much of each ingredient goes in and what happens to each ingredient (some might evaporate, some might be left in the bowl, etc.), you can figure out how much of each ingredient ends up in the final cake and how much is lost. The Material Balance Method is like that. It tracks all the inputs (like raw materials) that go into a process and all the outputs (like products, waste, and emissions) that come out. By knowing the exact amounts, you can calculate how much of the material is released as emissions.

Simplified Material Balance Method

The Simplified Material Balance Method and may be more appropriate for entities that do not maintain and track refrigerant supply, and that have not retrofitted equipment to use a different refrigerant during the reporting period. This method tracks emissions from equipment installation, operation, and disposal, and is recommended for organizations that have contractors service their equipment (refrigerant equipment, fire suppression equipment, etc.). However, rather than tracking every detail, you use general estimates. With this method, you take the total amount of material (refrigerant, fire suppression gas) in the system and assume a typical percentage might leak out each year (like an average rate). You also estimate how much might be lost when the equipment is retired (what may be remaining within the equipment as it gets thrown away). This gives you a quick, albeit less precise, estimate of emissions and works best for situations where you need a fairly good estimate but do not have detailed records.

Back to the cake – let’s say you don’t need to be so precise with your cake. You just want a rough idea of how much of each ingredient ends up in the cake versus how much is lost. So, instead of tracking every tiny bit, you make some reasonable assumptions to simplify the process. The Simplified Material Balance Method works similarly. It’s a quicker, less detailed version of the full Material Balance Method. It uses approximations or averages to estimate emissions, which is useful when you need a general idea rather than exact numbers.

Screening Method

The Screening Method is the quickest way to generate a rough guess of your emissions from source equipment (refrigeration and air conditioning equipment, fire suppression equipment) based on common industry knowledge. This method uses standard factors or averages that experts have developed, based on typical equipment and operating conditions. Rather than measuring or estimating anything yourself, you simply apply these standard numbers to get a rough idea of emissions. This works best for early stages of assessing emissions or when you just need a ballpark figure to see if you should investigate further.

This method is more like checking a list of common ingredients in cakes to see if your recipe might include something problematic, like too much sugar. Instead of calculating exactly how much of each ingredient is used, you’re just looking for warning signs.

The Screening Method is a very quick and basic way to estimate emissions. It’s typically used as a first step to identify whether emissions might be a concern. It involves simple calculations or even just looking at whether certain high-emission materials are involved. If the screening suggests a potential issue, you might then use a more detailed method like the Material Balance Method.

In summary:

- Material Balance Method is detailed and accurate.

- Simplified Material Balance Method is quicker and less precise.

- Screening Method is the quickest and is used to identify potential issues.

By understanding the importance of accurate reporting under the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program and various emission types and calculation methodologies, you can better support your organization’s journey in in accurately quantifying its GHG emissions.