This article includes reference to the following concepts: net-zero, gross zero, carbon neutrality, and carbon offsetting.

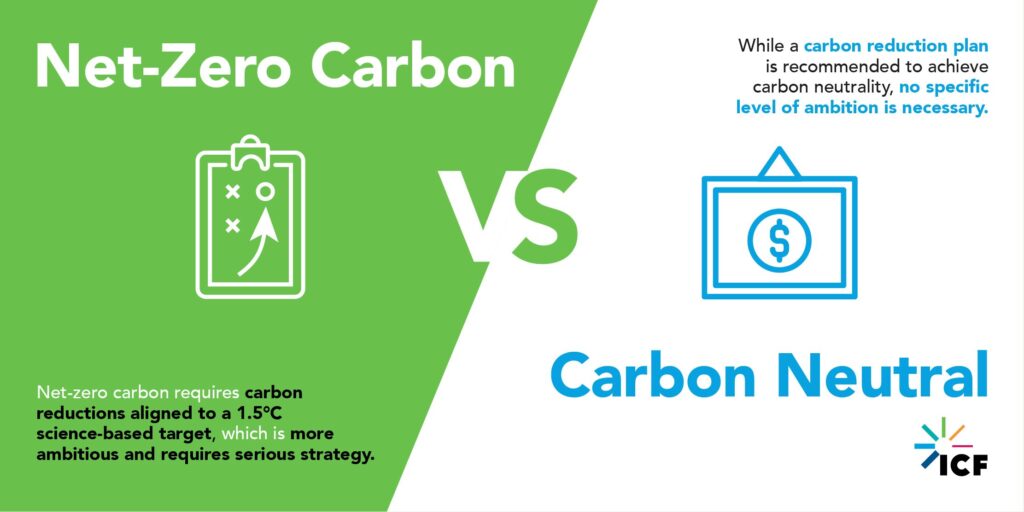

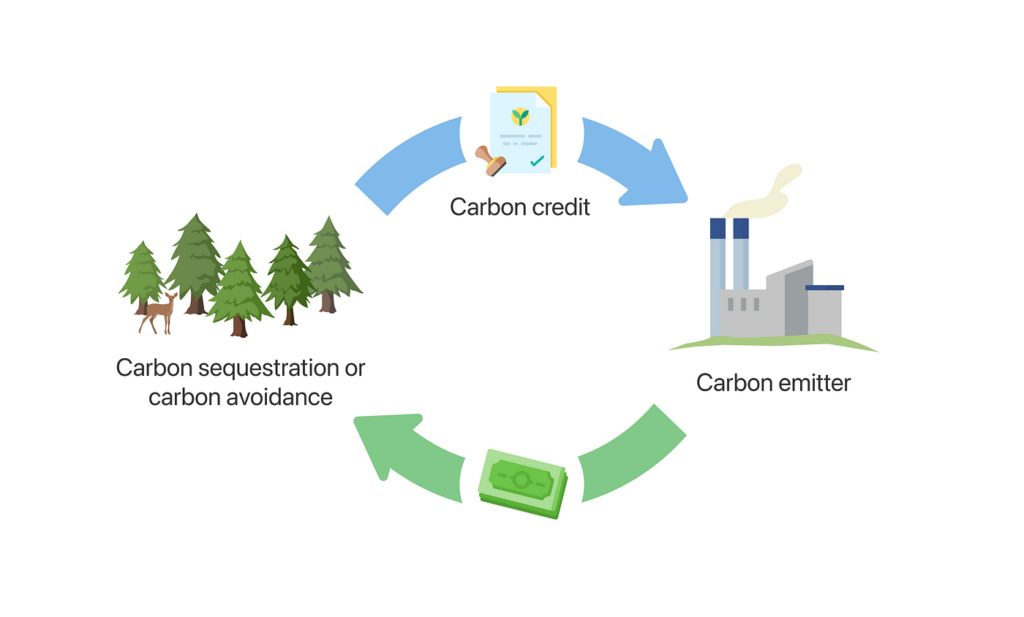

The term ‘carbon neutrality’ grew in prominence after the Kyoto Protocol (1997), which established market-based mechanisms to encourage both countries and private companies to reduce emissions. It established greenhouse gas reductions as a new commodity where emission-reduction (or removal) projects earn credits (each equivalent to one metric ton of carbon dioxide) that can be measured, tracked, and traded. With this, the carbon offset was born. But there’s another term that’s commonly confused with ‘carbon neutral’: ‘net-zero carbon’.

Source: https://www.icf.com/insights/environment/net-zero-carbon-versus-carbon-neutral

What Does Net Zero Actually Mean?

Net-zero carbon is linked to the Paris Agreement (2015), which aims to limit the rise in global temperatures below 1.5°C. — a goal that requires more ambition and serious strategy. To meet the Paris Agreement target, global carbon emissions will need to reach net zero by 2050.

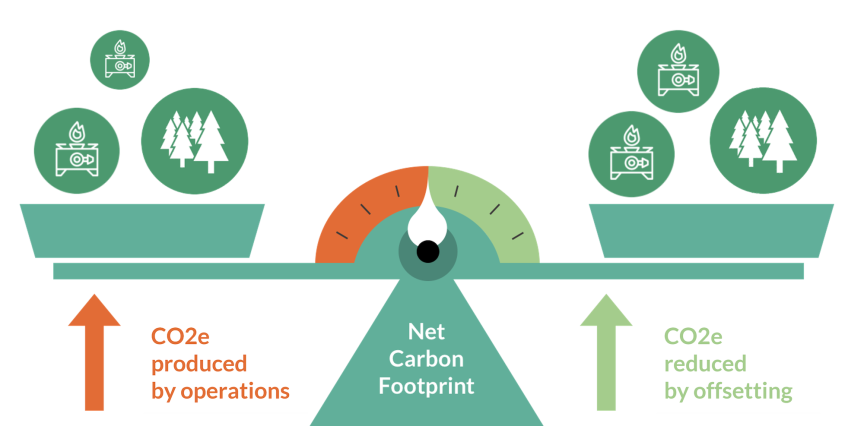

Imagine a giant balance scale. On one side of the scale, you have all the greenhouse gases (like carbon dioxide) that people release into the air by doing things like driving cars, making stuff in factories, and powering homes with fossil fuels. This is like adding weights to one side of the scale.

On the other side of the scale, you have ways to remove those gases from the air, like planting trees (they suck up carbon dioxide) or using special machines that can capture carbon. This is like taking weights off the scale.

Net zero means that the global scale is perfectly balanced. We’re still putting some greenhouse gases into the air, but we’re removing an equal amount. So, overall, we’re not adding to the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Gross Zero

Gross zero is the absence of all greenhouse gas emissions. This means that zero greenhouse gases are being produced at all, rather than offsetting them afterward through planting trees or other methods. This means stopping all greenhouse gas emissions entirely—no emissions at all. Think of it like trying to live without creating any waste ever. It’s super strict! For example:

- No cars running on gas.

- No factories producing emissions.

- No energy from coal, oil, or gas.

Everything would need to be powered by renewable energy like wind, solar, or hydropower, and there wouldn’t be any emissions left to balance out. It’s an ambitious goal, but in many cases, it’s nearly impossible to achieve 100% zero emissions.

Net Versus Gross

In effect:

- Gross Zero = No emissions at all.

- Net Zero = Balancing emissions (some emissions happen, but they’re offset).

Net zero is much more flexible. Instead of eliminating all emissions, net zero allows some emissions to still happen, but those emissions are balanced out by removing an equal amount from the atmosphere.

For example, a factory might still release emissions, but the company could plant trees or invest in technology that captures carbon from the air to “cancel out” their pollution. Think of it like eating a slice of cake but burning off the calories by exercising—it’s not about stopping entirely but balancing things out.

Gross zero is like saying, “I’ll never eat cake again—ever.” It means completely cutting out all the calories (or in this case, greenhouse gas emissions) and never letting them happen in the first place.

Net zero is like saying, “I’ll still eat cake, but I’ll go for a run after to burn off the calories.” It’s not about completely stopping emissions (or cake-eating), but balancing them out so there’s no overall effect.

In effect:

- Gross Zero = No cake, no calories, no emissions—at all.

- Net Zero = You eat cake but burn off the calories later to keep things balanced.

Carbon Neutral Versus Net Zero

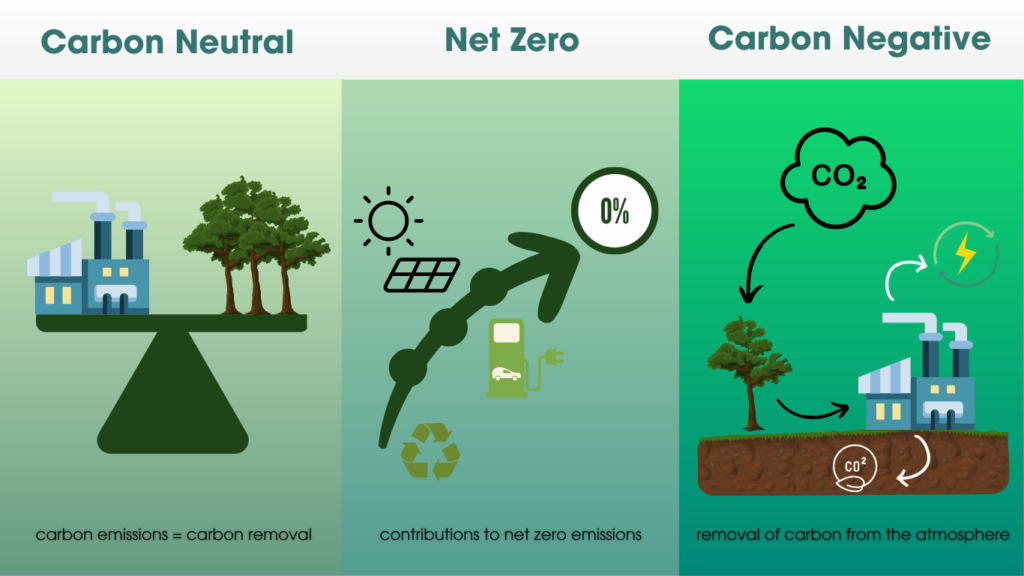

The difference between carbon neutral and net zero lies in how broadly they address greenhouse gas emissions and the goals they aim to achieve.

CO2 is one type of greenhouse gas, albeit a very important one. All GHGs are expressed in tons of CO2e. CO2e represents carbon dioxide equivalent and it serves as the common measurement unit in carbon accounting and other climate-risk concepts like carbon markets and carbon credits. For example, even if measuring a different gas (like methane), for the purpose of comparability, the emissions are expressed using CO2e.

Carbon Neutral: This means balancing out the amount of carbon dioxide (CO₂) a person, business, or activity emits by removing the same amount elsewhere (like planting trees or funding renewable energy projects).

Net Zero: This is a bigger commitment. It means balancing out all greenhouse gases (like CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide) emitted.

In summary:

- Carbon Neutrality: Just carbon.

- Net Zero: All greenhouse gases.

Why is the distinction important? Because carbon neutrality does not necessarily lead to a reduction in overall emissions.

Being carbon neutral does not mean a company produces zero emissions. It means the company is offsetting (i.e. balancing out) whatever they emit by purchasing some sort of credit elsewhere. Imagine eating a cake with 40 grams of sugar in it. Then going to the gym for 2 hours to try to burn it off. Even if somehow you burned off the exact number of calories you consumed by eating the cake – the ripple effects of the sugar in your body are already taking it’s toll.

Burn Now, Pay Later – Offsetting to Reach Net Zero

Even if, starting tomorrow, every company in the world offset every ounce of carbon it emitted, technically it would not decrease the overall amount of carbon in the atmosphere – it would simply stay as-is.

Furthermore, that kind of accounting still allows for the release of carbon into the atmosphere – along with all the ripple effects that come with it. Many believe that a true “removal” should include technologies that are permanent (able to store carbon for several centuries) and have a low risk of reversal, believing that activities such as carbon sequestration in soil, and forest restoration are not suitable to counterbalance companies’ carbon emissions.

Here’s how carbon offsets work using the cake analogy:

Imagine you eat a big slice of chocolate cake, and now you’ve got extra calories in your body (just like greenhouse gases in the atmosphere). Instead of skipping the cake altogether, you decide to balance it out by going for a run, swimming, or doing some extra chores to burn off those calories.

In the same way:

- Eating the cake = releasing greenhouse gases (pollution).

- Running or swimming = carbon offset projects, like planting trees or building wind farms, to “cancel out” the pollution.

You’re not avoiding the cake (or pollution), but you’re doing something extra to make up for it. Sort of.

The concept of “burn now, pay later” highlights the reality of relying on carbon offsets without first reducing emissions. It’s like eating cake every day and thinking you can always outrun the calories later.

While carbon offsets are helpful for balancing out emissions, they shouldn’t be used as an excuse to delay cutting back on pollution.

Offsets can fund valuable projects, like planting forests or building renewable energy, but they don’t erase the harm caused by emitting greenhouse gases in the first place. Plus, some offsets take time to show results—for example, a tree planted today may take decades to absorb the promised amount of carbon.

To truly tackle climate change, the focus must be on reducing emissions at the source first and using offsets only for the emissions that are nearly impossible to eliminate. Otherwise, it’s like running on a treadmill while the cake pile keeps growing.

The bottom line: Offsets are a helpful tool, but they’re not a free pass to keep polluting.