Introduction

After you’ve secured organization support, and before you start collecting emissions data, you’ll need to establish clear boundaries for your greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory. The inventory will provide the foundation for your company’s climate change strategy by enabling you to identify reduction opportunities, set reduction targets, and track progress over time. When developing a GHG inventory, a company should first establish its organizational boundary before determining its operational boundaries.

Organizational Boundaries

For the purposes of financial accounting, legal and organizational structures within businesses are treated according to established rules depending on the structure of the organization and the relationship among relevant stakeholders. Similarly, in setting organizational boundaries for a GHG inventory, companies select their approach and apply it consistently across the organization for the purpose of accounting and reporting emissions.

For corporate reporting, the two main consolidation approaches outlined by the GHG Protocol are the equity share and control approaches. If the reporting company wholly owns all its operations, its organizational boundary will be the same, regardless of the chosen approach. Popular examples of a reporting companies that own much of their operations are Apple, Amazon, and General Electric. Apple owns its own designs, hardware, operating systems, and software, instead of relying on other companies to supply them. Amazon owns its own warehouses and transportation fleet, which allows it to deliver its products directly to customers. General Electric owns its own warehouses and transportation fleet, which allows it to deliver its products directly to customers. For those operations, the parent company’s organizational boundary will be the same for both equity share and control approaches to GHG reporting. Examples of wholly owned subsidiaries include Google’s ownership of YouTube, Facebook’s ownership of Instagram, and Amazon’s ownership of Whole Foods.

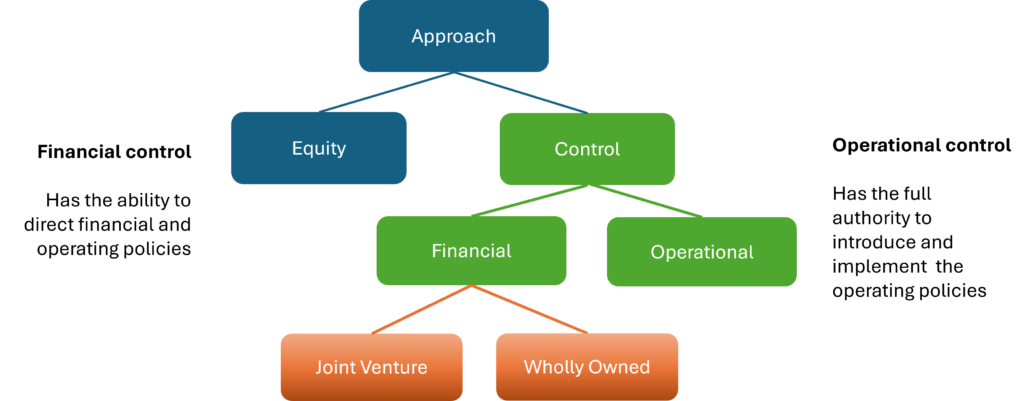

Approaches for selecting a boundary for a company’s GHG inventory

With the equity share approach (which cannot be used by financial institutions following PCAF), a 60% equity stake means the reporting company must account for 60% of the emissions of that subsidiary. Within the control approaches, companies have two options – financial control or operational control methodologies. With the financial control approach, if a reporting company has the ability to direct financial and operating policies, the reporting company must include that subsidiary in their own GHG inventory. A company is considered under the financial control boundary if it retains the majority of risks and rewards of ownership of the operation’s assets and has overall control of financial policies. It does not necessarily mean the company is a majority owner in an organization. With the operational control approach, if a reporting company has the authority to implement operating policies, the reporting company must include that subsidiary in their own GHG inventory. An operational control boundary approach is considered when an organization or one of its subsidiaries has full control over the operational day-to-day policies of a company. It extends beyond financial control to encompass direct operational management.

The GHG Protocol has specific guidance for leased assets, outsourcing, and franchises. If a company elects to use the equity share or financial control consolidation approaches, the lessee only accounts for emissions from leased assets that are treated as wholly owned assets in financial accounting and are recorded as such on the balance sheet (i.e., finance or capital leases). If a company chooses to use the operational control consolidation approach, the lessee only accounts for emissions from leased assets that it operates (i.e., if the operational control criterion applies).

Let’s take a deeper dive into these consolidation approaches.

Equity Share Approach

The equity share approach is typically more straightforward of the two approaches. Under the equity share approach, a company accounts for GHG emissions based on its economic interest in an operation, typically aligned with its ownership percentage. This approach ensures that the share of emissions reflects the company’s actual economic risks and rewards. This may require consultation with accounting or legal teams.

BP is an example of a reporting company that uses the equity share approach for their GHG inventory boundary, aligning closely with the company’s financial accounting procedures. BP’s equity share boundary includes all operations undertaken by BP and its subsidiaries, joint ventures, and associated undertakings as determined by their treatment in the financial accounts. Fixed asset investments, i.e., where BP has limited influence, are not included. Reports are verified by independent auditors.

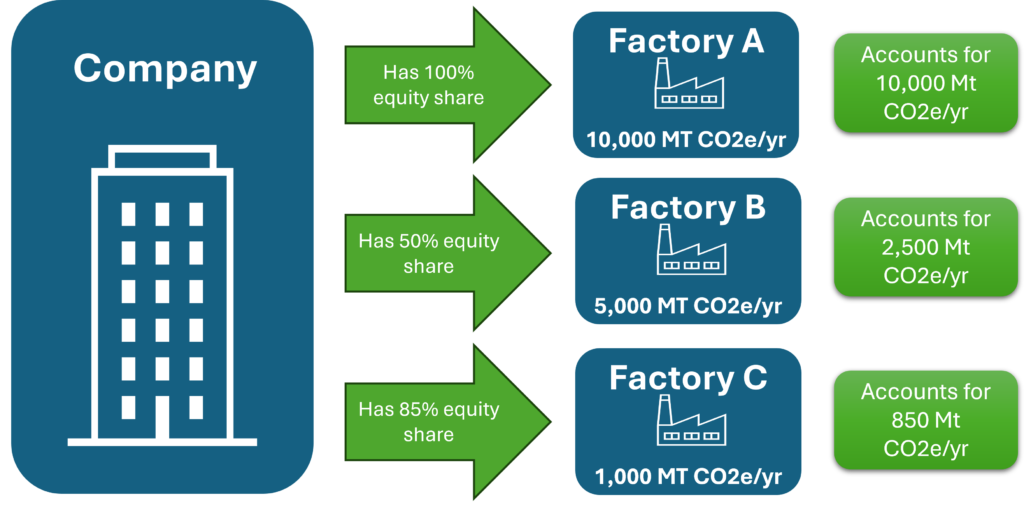

Equity share approach for establishing boundaries for a GHG inventory

In the above scenario, the company is responsible for the emissions of each factory proportional to its equity share. The company in this case is responsible for 100% of Factory A’s emissions, 50% of Factory B’s emissions, and 85% of Factory C’s emissions, for a total of 13,350 Mt CO2e per year.

Control Approach

Under the control approach, a company accounts for 100% of the GHG emissions from operations it controls, excluding emissions from operations it has an interest in but does not control. Control can be defined either financially or operationally. Companies must choose between these criteria, considering the best alignment with emissions reporting and trading schemes and their actual power of control.

Financial control exists when the company has the authority to allocate or divert money towards certain operations over others. In this scenario, whoever controls the flow of finances to a certain operation or facility, is responsible for the emissions of that operation. For example, if BP decides the annual budget for a certain refinery, including how much money to allocate to maintenance, upgrades, and expansions – then they are also responsible for the emissions from that specific refinery.

Operational control exists when the company has the authority to introduce and implement operating policies. In this scenario, whoever controls operational decisions is responsible for the emissions of that operation or facility. For example, let’s say Dow Inc. operates a chemical manufacturing plant, but it only owns 40% of the plant, while various other companies own the remaining 60%. Despite owning less than 50%, Dow Inc. has been designated as the operator of the plant. This means it has operational control over the plant, including implementing operating policies, such as safety protocols and quality control procedures, and managing operations, such as hiring staff and making decisions about how the plant runs on a day-to-day basis. Under this model, regardless of ownership percentage, Dow Inc. would be responsible for the emissions of that manufacturing plant.

The following examples outline different calculations that would be applied for different scenarios under the control approach.

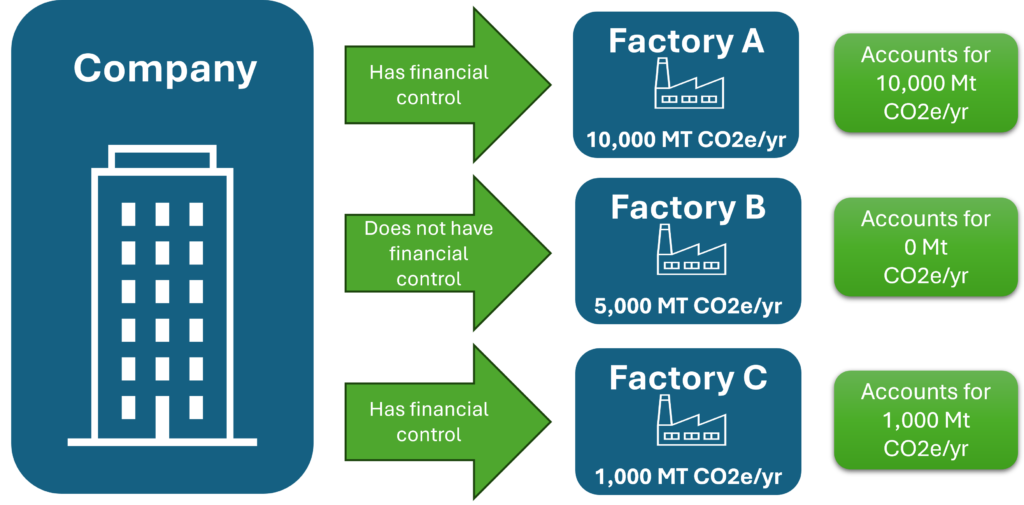

Financial control, wholly owned

Financial control, wholly owned approach for establishing boundaries for a GHG inventory

In this scenario, any factory under financial control of the company must be included in the company’s GHG inventory. In this case, that pertains to Factory A and C, for a total of 11,000 Mt CO2e per year.

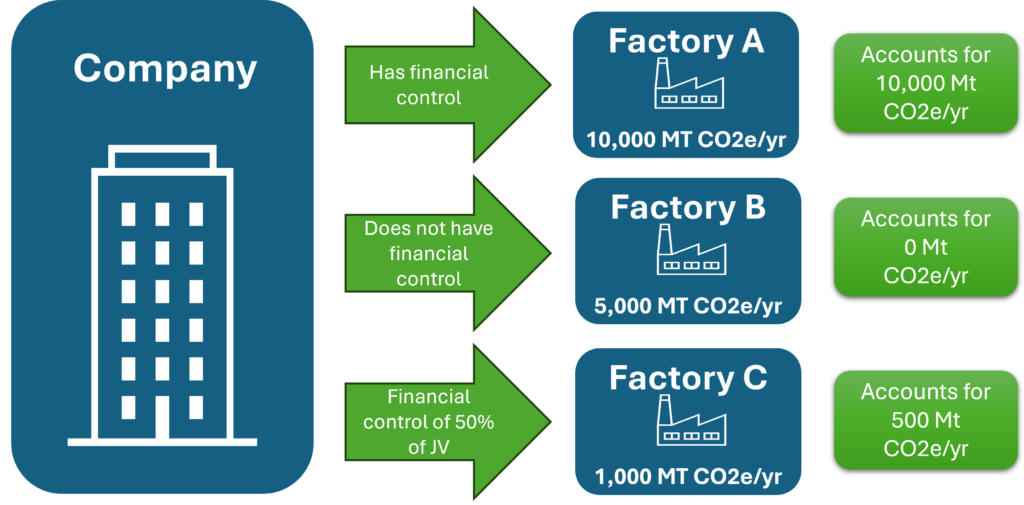

Financial control, joint venture

Financial control, joint venture approach for establishing boundaries for a GHG inventory

In this scenario, a company’s responsibility for their GHG inventory boundary as it relates to joint ventures is dictated by how much of a joint venture the company has financial control over. In this case, that pertains to 100% of Factory A and 50% of Factory C, for a total of 10,500 Mt CO2e per year.

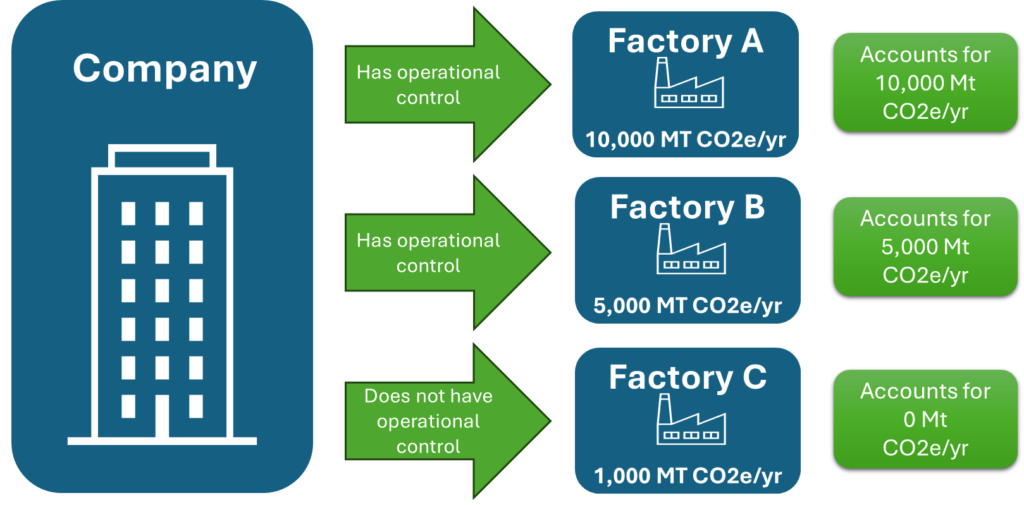

Operational control

Operational approach for establishing boundaries for a GHG inventory

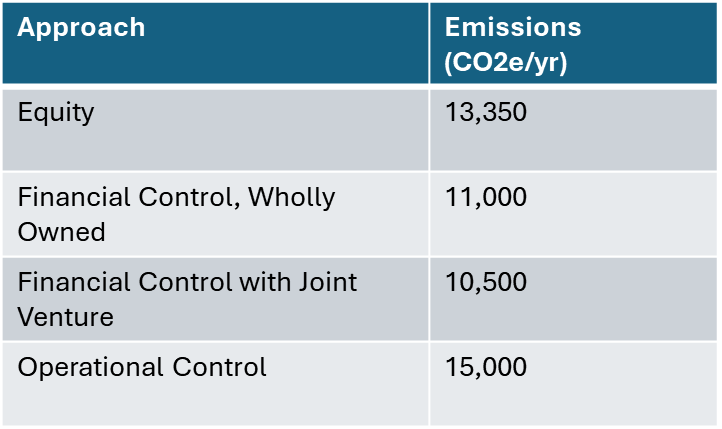

Emissions Summary by Approach

Adding up Factories A, B, and C yields the following emissions totals in CO2e per year for each approach mentioned:

Cue collective gasp – but Dani, they’re all different! Yes, yes, they are. The question is – why?

Well, the answer is because we failed to consider one very important thing before calculating our organizational boundaries – our operational boundaries.

More boundary considerations?! Yes, more boundary considerations!

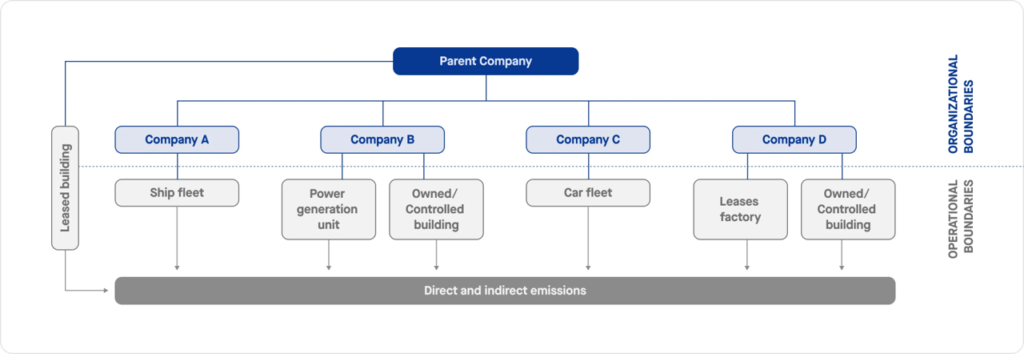

Operational Boundaries

Operational boundaries in the context of carbon accounting define the extent and parameters within which an organization measures and manages its GHG emissions. At a very basic level, the GHG Protocol classifies emissions into two general categories – direct and indirect. Direct emissions occur from sources that are owned or controlled by the reporting entity, such as those from combustion in owned or controlled boilers, furnaces, and vehicles. We call these scope 1 emissions. Indirect emissions occur from sources that are owned or controlled by an entity other than the reporting entity (such as a federal agency i.e. utility company for scope 2 or a partnering company such as a supplier for scope 3), but are still a consequence of the reporting entity’s operational activities. Scope 2 and 3 emissions are both indirect sources, with scope 2 encompassing purchased electricity and scope 3 referring to a company’s value chain emissions.

An operational boundary defines the scope of direct and indirect emissions for operations that fall within a company’s established organizational boundary. The operational boundary (scope 1, scope 2, scope 3) is decided at the corporate level after setting the organizational boundary. By establishing organizational boundaries first, the reporting company ensures that all relevant operations are included in its GHG inventory before identifying and categorizing the specific emission sources within those operations.

The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard is designed to prevent double counting of emissions between different companies within scope 1 and 2. By following the protocol, companies can minimize the risk of counting certain emissions within their own inventory that another company has already included in theirs. This requires clear communication between companies to understand what each organization is including within their own inventory and why.